Abstract

This paper investigates the concept of resilience at personal, organisational and industry levels. The pandemic has made people feel vulnerable, out of control and repressed. Some industries have thrived and others hemorrhaged, needing to pivot and adapt to survive. Australia’s geographic isolation has acted as a buffer and a point of differentiation from many other countries but did not provide immunity. Individuals have emerged from the COVID-19 with a different mindset, changed expectations about what they want from work and a different outlook to life generally. Workplaces continue to be disrupted as worker sickness rates escalate, a phenomenon dubbed ‘quiet quitting’ takes hold as workers prioritise other parts of their life and the ‘Great Resignation’ decimates the intellectual and social capital within some teams and organisations.

To keep staff, companies need to adapt as workers have now placed a higher level of importance on their health and wellbeing and are looking for a sense of meaning in what they do as well as ways to feel connected and that they are giving back and multiple disciplines and argues that resilience at all levels, across disciplines and industries is required to thrive in the future. An industry- based model for sustainability- innovation-resilience is examined to help industries respond to megatrends and future pandemics. Within this model, industries are called upon to enliven their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), and career development for staff to support staff wellbeing, providing a path forward to a healthier approach to work and wellbeing.

Keywords

Health, COVID-19 impact, resilience, workplace health promotion, sustainability-innovation- resilience, corporate social responsibility, megatrends.

Introduction

At every level of society, a state of flux has taken hold and with it uncertainty, rapid change and evolution, requiring a new approach to how individuals prioritise what is important in life and how corporations respond to their staff. In Australia, the relationship between resilience and vulnerability has been observed as the pandemic progressed, and physical, economic, social and environmental determinants of vulnerability have impacted individual’s resilience, mental health and wellbeing. The pandemic has made people feel involved in their community.

The pandemic has been noted to result in diminished mental health, particularly in individuals already predisposed to mental health issues and amongst individuals with less coping skills. At a community level, resilience and vulnerabilities can either protect individuals, or expose them to ongoing risks. Government and industry policies influence how pre-existing vulnerabilities may be mitigated or exacerbated, and how new groups may develop vulnerability; thereby shaping how vulnerable communities are identified, the degree to which the vulnerable can flourish, or the degree to which newly or existing vulnerable communities become distressed in response to crisis.

Resilience has been defined as, ‘bungee jumping through the pitfalls of life meaning the ability to overcome adversity and challenging life events. Resilience harnesses an array of skills and dispositions including perspective taking, conflict resolution, negotiation and self- regulatory skills. The preferred concept of resilience skills adopted in this paper is that in coping with adversity a person does not just return to their previous state, but rather, evolves to a new state made possible by ongoing reflection, learning and recursive personal growth.

The repertoire of social-emotional skills involved in resilience draws on the science of positive psychology, meaning an individual levers their psychological assets to face the challenging situation. One of the recognised proponents of positive psychology, Martin Seligman (2011), has developed a theory of well-being as a construct of five measurable elements, referred to as PERMA: positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and 2O’Connor et al., 2020

Polonsky & Weber 2022 achievement. Each element of PERMA needs to be harnessed to deal with the level of disarray experienced from the crisis of the pandemic. To have health, freedom and life as it is known suddenly ripped away requires a person to ‘pull out all the stops’ and focus on what can be controlled such as maintaining positive social connections via the use of technology, physical activity and maintaining quality sleep and nutritional approaches as well as maintaining key positive relationships.

Individual, community and corporate resilience

During the pandemic individuals had what they usually do not – time and they practiced introspection and ran audits of what brings meaning to life. Governments developed ‘policy- on-the-run,’ and corporations were polarised with responses ranging from focusing on getting through the storm of the pandemic and just surviving, to trying to keep staff working and endeavouring to meet a burgeoning demand in those industries focused on e-commerce. There is no denying the deleterious impact that COVID-19 exerted on global capital markets. It was noted the severity of outbreaks correlated with an inverse relationship impacting stock markets and industry.

However, an interesting parallel was developing. Just as individuals recoiled, so did corporations. The parallel to individual resilience became evident in organisations, as a framework reliant on the processes of preparation, perceiving and propelling were unveiled to address the challenge.

The business response which makes sense must involve a sense of urgency evident in the degree of responsiveness with which all industries must be ready to, adapt to, and take action. The pandemic is one crisis of numerous expected, constituting not only the continuation of future pandemics but also the result of megatrends such as climate change taking effect. Given these facts, resilience is a vital skill-set and way of responding to future challenges, requiring a multifaceted strategy inclusive of adaptability. (Walker et al., 2006) state: “resilience is the capacity of a system to experience shocks while retaining essentially the same function, structure, feedback, and therefore identity.” (Folke et al.,2010) define resilience as “[t] he capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure and feedback, and therefore identity, that is, the capacity to change in order to maintain the same identity”.

Resilience as a term emerged in the 1970s in ecological science to explain how a system responds to and recovers from disruption (Holling, 1973). It has been appropriated across industries such as tourism where it fits neatly with sustainability as a conceptual model through to education and the application of psychology for staff and student wellbeing and systems thinking in ecology and the science-based industry (McCool et al., 2015), in technology and more generally all of the business sector (OECD, 2020). The resilience concept encompasses an inclusive and integrative “social ecological systems” approach which gives it a firm interdisciplinary underpinning in its application appropriated across industries. Resilience is a vital feature of complex, dynamic systems evident across disciplines including psychology (Fuller, 2003), economics (Arthur, 1999), ecology (Folke et al., 2002), pedology (Thurston, 2021), and network theory (Calloway et al., 2000) and sociology (Adger, 2000). No longer can organisations operate in silos and so adopting approaches to project management, restructures to implement new roles and ways of working to enhance durability and adaptability is necessary.

Today, the concept of resilience systems (SES), providing a theoretical underpinning towards developing new ways to address unstable and chaotic systems (Becken, 2013; Cochrane, 2010). The concept of resilience requires adaptive alternatives to address threats from a full range of natural or human- induced crises and uncertainties, including those precipitated by frequent unpredictable events and longer term incremental hazards associated with climate and economic change. Resilience demands adaptability, flexible thinking and behaviour and systems thinking within the wider socio-ecological system (Cochrane, 2010; Lew, 2014). However, while resilience can be considered an attribute that mitigates uncertainty and unpredictability through the adoption of adaptive social and business practices, change must be considered through the SES lens (McCool, et al., 2015). Insufficient acknowledgement of deep complexity can lead to unexpected outcomes, resulting in “more problems, less resilience and to [the undermining of] developmental trajectories” (McCool et al., 2015).

New approaches to retain and develop staff

Changes to workplaces mandated by lockdowns, changes to workplace structures and ways of working including new hybrid models means flexible, staff-focused inclusive work environments have found their way into the mainstream. As more workers than ever before have resigned without new jobs to go to, opted for remote work and pushed back against employer demands corporations realise the status quo has altered and they need to adapt to retain and develop staff. Lack of opportunity has been cited as a major reason why staff resign and therefore a strategy gaining momentum is for companies to promote staff to more senior roles from within the organisation and to make it known that is the preferred approach. This can act as a motivator for staff who want to advance themselves and develop their career.

Giving back, reciprocity (Fremeaur, 2011) and philanthropy can sound removed from the business world, but on the contrary, business organisations are a community (albeit profit making focussed) with a corporate social responsibility (CSR) by which they not only add value, but increase revenue. In return for good deeds, customers and clients want to support organisations that “do good” (Morgan, 2021; Baines, 2015) and the resulting increased business and positive reputation in the marketplace enables a “win-win” (Fisher & Ury, 1968). Psychologically, giving back, volunteering or supporting others can enhance staff’s sense of purpose and positive affect; thereby helping to retain staff and attracting talent (Haski-Leventhal et al., 2019).

Ethical values-based practices, acknowledging and rewarding staff and increasing employee’s engagement through creative work can support organisations‘ efforts to develop their staff and ensure they gain job satisfaction (Valentine, 2010). Therefore, the opportunity for staff to volunteer or give back to their community is significant by increasing engagement, reducing stress (Gallup, 2022) and providing a flexible as well as balanced workplace. CSR can, therefore, fulfill the purpose of a health promotion strategy when staff are involved in ways that add meaning to what they do and provide an increased locus of control.

Sustainability, innovation and resilience as interdependent and reflexive concepts

Alternatively, addressing the concepts of sustainability, innovation and resilience separately is remiss, as these concepts are interdependent and intersect in ways which need to be novel, creative and efficient, in order to rebound from the pandemic and make a difference to individuals and the planet of the future (Hargadon, 2015). The relationship is symbiotic in nature as well as reflexive, requiring each to mold and reshape as the others activate. The recursive and interactionist manner in which these three terms relate means that it will likely become more common in the future to refer to innovation as “sustainable innovation” or “eco-innovation.” This trend acknowledges that silo approaches to managing crises and people affected are being replaced by divergency and multidisciplinary approaches which draw together different interests.

The surge of activity to develop smarter ways of overcoming adversity also requires nimble analysis of impacts on the environment, individuals and the community. This necessitates drawing on less environmental resources, examining the health and wellbeing impacts.. Moreover, an equally significant notion is that of replicating innovative endeavour at a sustainable pace (Hargadon, 2015). Historically, examples of corporations demonstrating a sense of social responsibility can be traced to the early 1800s when factories in Great Britain changed some conditions to improve the workers’ lives, aiming to increase their productivity (Riccio, 2019); thereby, acting resiliently.

Corporate social responsibilities were formalised in the 1970s evident in the statement; “business functions by public consent and its basic purpose is to serve constructively the needs of society — to the satisfaction of society” meaning organisations should take responsibility to contribute beyond goods and services (US Committee for Economic Development (CED), 1971) Today, social responsibility is an expected part of a corporate’s identity and is an important opportunity for increasing staff engagement and collegiality.

Globally, the pandemic, the slowing economy, and the war in the Ukraine activated a range of drivers affecting resilience themes. These events emphasised the need for resilience in unison with sustainability and innovation. For example, leveraging the resilience framework of “prepare, perceive and propel” entailed organisations building buffers by maintaining higher than usual stock supplies, creating scenarios and playing out second tier options and pivoting from rapid changes to strategic plans could each position companies more favourably in the marketplace. (Brande & Sternfels, 2022) Organisations not able to adapt vanished as the supply chain was negatively affected, staff availability was squeezed and gaps in skills emerged, fuel prices increased and travel halted.

The World Economic forum (2022) research suggests that the impact of resilience (or lack of it) on annual GDP growth is 1 percent to 5 percent globally. Major challenges which need to be addressed through sustainability- innovation-resilience are varied covering basic needs through to policy, institutional and legal reform. The basic needs include food, shelter, sanitation and health addressing inequity and making more ethically sound decisions.

Food scarcity, poor living conditions and over population require attention as fewer of the world’s population demand more of its resources to supply particular foods including meat and fast foods. The degradation of the environment, climate change and the resultant impact on different species and the ecosystem, energy use and the choice of fuels (Fiksel, 2006) means industry is pressured to produce more with less.

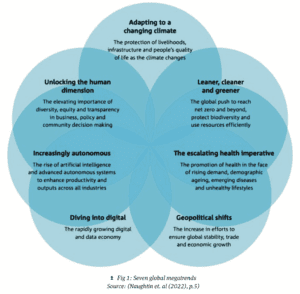

Meanwhile, geopolitical pressure and conflicting ideological and international tensions need to be managed. Peace and security are paramount to safeguard development, economic and trade and international relations (Brundtland, 1987). These concerns are not dissimilar to the megatrends portrayed by the CSIRO in Figure 1 and bring to light the need to value the contribution that individuals of different backgrounds can contribute.

Conclusion

The flip side to any challenge is the opportunity it brings. Models of resilience evident at the personal level through adopting positive psychology and personal skills, through to how government policy impacts vulnerable communities or provides a buffer together with operating in ways that are sustainable-innovative-resilient herald in new ways of thinking and doing, as a powerful learning from the pandemic.

Levering CSR initiatives and strategies can provide one effective way to harness goodwill and make a difference both for the recipients and for the staff in corporations involved in the implementation, while addressing local through to global concerns. As the future unfolds, the ways in which resilience is appropriated across industries and workplaces will continue to provide a powerful lens and mechanism for making sense of experiences.

References

Adger, W. (2000). ‘Social and ecological resilience: are they related?’ Progress in Human Geography, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 347–364.

Arthur, W. (1999). ‘Complexity and the economy’, Science, vol. 284, no. 5411, pp. 107–109.

Becken, S. & Wilson, J. (2013). ‘The impacts of weather on tourist travel’, Tourism Geographies, vol. 15, no. 4,

- 620–639.

Baines, P. (2015). Doing Good by Doing Good why creating shared value is the key to powering business growth and innovation, John Wiley & Sons Australia, Melbourne.

Brande, B. and Sternfels, B. (2022). ‘Resilience for Sustainable Inclusive Growth’, MicKinsey & Co, [Online]. Available:

https :// w w w.mc kinse y. c om/ b u s i n e s s – f u n c t i o n s / r i s k- a n d – resilience/our-insights/resilience-for- sustainable-inclusive-growth

Brundtland, G., (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future, United Nations General Assembly document A/42/427

Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future, [Online]. Available: http://www.un-documents.net/our- common-future.pdf

Callaway, D., Newman, M., Strogatz,

- and Watts, D. (2000). ‘Network robustness and fragility: percolation on random graphs’, Physical Review Letters vol. 85, no. 25, pp. 5468– 5479.

Cochrane, J. (2010). ‘The sphere of tourism resilience’, Tourism Recreation Research, vol. 35, no. 2,

- 173–185.

Fiksel, J. (2006). ‘Sustainability and resilience: toward a systems approach’, Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 14-21.

Fisher, R. and Ury, W. (1968). Getting to Yes, Penguin Books, London.

Folke, C. Carpenter, S. Elmquist,

- Gunderson, L. Holling, C. and Walker, B. (2002). ‘Resilience and sustainable development: building adaptive capacity in a world of transformations’, Ambio vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 437–440.

Fremeau, S. and Grant, M. (2011). ‘‘No Strings Attached’: Welcoming the Existential Gift in Business’, Journal of Business Ethics vol, 99, pp. 63–75.

Fuller, A. (1998). From Surviving to Thriving: promoting mental health in

younger people ACER, Camberwell.

Gallop (2022). State of the Global Workplace 2022 Report, [Online]. Available: https://www.gallup.com/ workplace/349484/state- of-the- global-workplace-2022-report.asp x?thank-you-report-form=1.

Guerra, N. Modecki, K. Cunningham, W., (2014). World Bank Group Developing Social-Emotional Skills for the Labor Market, The PRACTICE Model Social Protection and Labor Global Practice Group.

Hargadon, A. (2015). Sustainable Innovation – Build Your Company’s Capacity to Change the World, Stanford University Press, California, 1st Edition.

Haski-Leventhal, D., Kach, A., and Pourander, M. (2019). ‘Employee Need Satisfaction and Positive Workplace Outcomes: The Role of Corporate Volunteering’, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 593–615.

Holling, C. S. (1973). ‘Resilience and stability of ecological systems,’ Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, no 4, pp. 1–23.

Kairinos, N. (2022). ‘How to Prevent the Great Resignation’, ITNOW vol. 64 (2) pp. 12-

Lew, A. A. (2014). ‘Scale, change and resilience in community tourism planning’, Tourism Geographies, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 14–22.

McCool, S. F., Freimund, W. A. and Breen, C. (2015). Benefiting from complexity thinking. In Worboys, G. L., Lockwood, M, Kothari, A., Feary, S., & Pulsford, I., (Eds.), Protected area governance and management pp. 291–326, ANU Press, Canberra.

Morgan, B. (2021). 20 Companies That Use Their Profits For Social Good October 26, [Online]. Available: https://www.forbes.com/sites/ blakemorgan/2021/10/26/20- companies-that-use-their-profits-for-

social-good/?sh=1a175c8511a8

O’Connor, R. C., Wetherall, K., Cleare, S., Eschle, S., Drummond,

- and Ferguson, E. (2018). ‘Suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm: national prevalence study of young adults.’ British Journal of Psychiatry Open 4: pp. 142–148.

Masterton, V. (2022). ‘What is quiet quitting?,’ World Economic Forum September 2 [Online]. Available: https://www.weforum. org/agenda/2022/09/tiktok-quiet- quitting-explained/

Polonsky, M. and Weber, V. in Shultz, C J, Rahtz, D R, and Sirgy,

- M. Editors (2022). Community Quality-of-Life and Well-Being Lessons from Multi-Country Analyses of Global Pandemic, Springer eBook.

Riccio, J. (2019). ‘How big tech is giving back to society,’ PwC Australia [Online]. Available: h t t p s : / / w w w . p w c . c o m . a u / digitalpulse/tech-philanthropy- industry-giving-back-society.html. O’Connor, R. C. Wetherall, K. Cleare,

S. McClelland, H. Melson, A. J. Niedzwiedz, C.L. O’Carroll, R. E.

O’Connor, D. B. Platt, S. Scowcroft,

E. Watson, B.Zortea, T. Ferguson,

- and Robb, K. A. (2020). ‘Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study,’ British Journal of Psychiatry [Online]. Oct 21 pp. 1–8. Available: https:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC7684009/.

Shangzhi, Q. Jianing, J. Xinming, L. Ming-Hsiang, C. and Xina, Y. (2021). Can corporate social responsibility protect firm value during the COVID-19 pandemic?, International Journal of Hospitality vol. 93, Feb pp. 1-12.

Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish a visionary new understanding of happiness and wellbeing, Simon & Schuster, New York.

United Nations. (2004). Living with risk: A global review of disaster reduction initiatives. In United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, United Nations.

US Committee for Economic Development (CED) (1991). Social

Responsibilities of Business Organisations June 1991 [Online]. Available: https://www.ced.org/pdf/ Social_Responsibilities_of_Business_ Corporations.pdf.

Thurston, T. Lundstrom, K. and Gonzalez, C. (2021). Resilient Pedagogy. Pressbooks. [Online]. Available: https://oen.pressbooks. pub/resilientpedagogy/.

Valentine, S, Godkin, L, Fleischman, G, M. and Kidwell, R. (2011). ‘Corporate Ethical Values, Group Creativity, Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention: The Impact of Work Context on Work Response,’ Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 98, pp. 353–372.

Walker, B. H. Gunderson, L. H. Kinzig, A. P., Folke, C., Carpenter, S.

R. and Schultz, L. (2006). ‘A handful of heuristics and some propositions for understanding resilience in social-ecological systems’, Ecology and Society, [Online]. vol. 11, no. 1, 13. Available: https://www. ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/ art13/

Dr Michelle Nemec: AtivateXL, Australia

https://doi.org/10.57259/GRJ5071

BIO

Dr Michelle Nemec is from Sydney,Australia and she earned her PhD in educational psychology at the Australian Catholic University (ACU) Institute of Positive Psychology in Education as well as aa Juris Dr Law Degree and other postgraduate Masters degrees at the University of New South Wales. She is a member of the Faculty at Global Academy, an author and an inspiring and compelling Keynote speaker.